Maintaining manufacturing when the chips are down

The global semiconductor shortage is expected to last at least another year as rising demand proves relentless. So what are the plans to boost supply capacity?

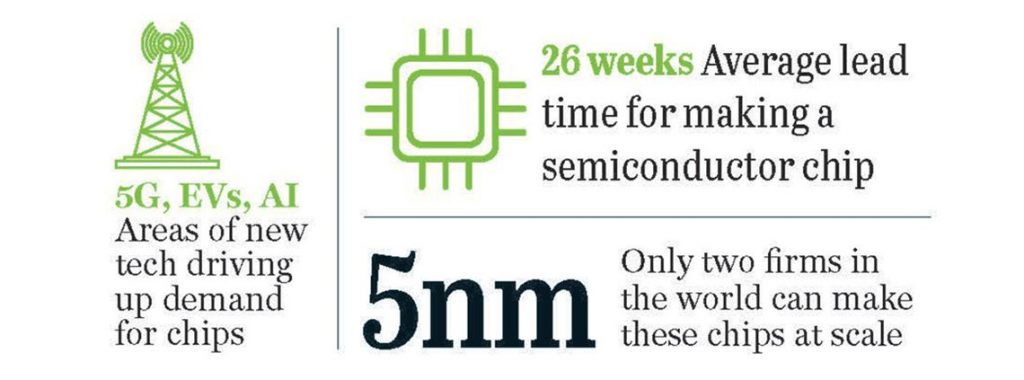

The global semiconductor supply chain was under strain long before the pandemic, on the back of rising use of smartphones, the rollout of 5G and the growth of the Internet of Things and electric vehicles. And it’s this hunger for devices that has led to price increases, as suppliers prioritised more profitable orders or bigger customers. Tension between the US and China brought the issue into sharp focus, as semiconductors are vital to both countries’ economies and security.

Covid-19 only exacerbated this situation, creating an almost-instant surge in demand for laptops and smartphones to support the switch to remote working, while more disposable income prompted many to splash out on home technology comforts.

Then came a double hit of a storm in Texas, in February, which shut down factories and led to manufacturer Infinion warning all its chips were effectively reserved for the next 12 months, followed by a factory fire in Japan, in March. The fire hit one of the world’s leading semiconductor producers, Renesas, and 23 machines were destroyed. By the end of May, the factory was still only operating at 88% capacity; bad news for the automotive sector, as Renesas produces nearly a third of the chips used in cars globally.

Which sectors are worst affected?

The chip shortage has had a huge impact on the automotive industry. Carmakers including Jaguar Land Rover, Mini, Ford and Volkswagen have all been forced to temporarily shut production sites around the world as they grapple with supply issues. Stellantis, which owns Fiat, Chrysler, Peugeot, Citroën and Vauxhall, has reduced operations in eight of its 44 factories, resulting in 190,000 fewer cars being produced than it had anticipated in the first quarter of this year.

In April, the situation was summed up by Tesla boss Elon Musk, who, in his typically no-nonsense approach, said the firm had been facing “insane difficulties” in its supply chain, including global chip shortages. Meanwhile, consultancy AlixPartners predicted in March the chip shortage would mean the automotive industry losing out on $110bn in potential sales this year, while Ford estimated it would result in a $2.5bn hit to earnings.

While not all sectors have yet felt the full impact of shortages, Sundar Kamak, head of manufacturing solutions at Ivalua, believes engineering, construction and energy firms could all feel the pinch in supply in the near future, due to the need for chips in microcontrollers.

“These can be used for critical tasks like monitoring pipelines for gas leaks, or temperature control for machinery,” he says. “This could potentially shut down production for engineering, construction, and oil and gas firms as they struggle to find replacement parts quickly.”

The microcontroller shortage is already having an impact on some products including washing machines and smart toasters, and less common equipment such as electronic dog-washing machines.

How long will it last?

Glenn O’Donnell, vice-president, research director, at advisory Forrester, said the firm expected the shortage to last into 2023, due to continual high demand and restricted supply. In a blog, O’Donnell said: “The PC surge will soften a bit in the coming year but not a lot. Data-centre spending will resume after a dismal 2020, and edge computing will be the new ‘gold rush’ in technology.

Couple that with the unstoppable desire to instrument everything, along with continued growth in cloud computing and cryptocurrency mining, and we see nothing but boom times ahead for chip demand.”

The Financial Times, meanwhile, is slightly more optimistic and reports Singapore-based manufacturer Flex, which makes chips for companies including Ford and HP, as forecasting shortages lasting until mid-2022, and potentially into 2023. Research firm Gartner suggests supply could return to normal levels by the second half of 2022, although it could take until the end of next year before supply chain disruptions are overcome.

But there’s also the potential the pandemic is not done with us just yet, in terms of its impact on the semiconductor market. Taiwan – the world’s leading foundry market – has been battling to stay on top of a Covid-19 outbreak since May, and is also facing its worst water shortages in more than 50 years.

Taiwan is important as its contract manufacturers together make up more than 60% of total global foundry revenue last year, according to data by Taipei-based research firm TrendForce. Much of this is due to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which accounted for 54% of total foundry revenue globally in 2020.

“There was a lot of concern in Taiwan that droughts or the resurgence of a new Covid outbreak could result in a significant shortfall in production,” says Andrew Tilton, chief Asia economist at Goldman Sachs. “So far we haven’t seen that.”

What is being done?

In the longer term, greater capacity will alleviate shortages but this could still be several years down the line. The EU has announced plans to double its share of semiconductor production from 10% in 2020 to 20% in 2030, as part of its Digital Decade initiative. For this it intends to invest €20-30bn, and has already seen its market share increase from 6% just five years ago.

Chipmaker Intel is boosting manufacturing capacity to meet demand, including investing $20bn in two new factories in Arizona. TSMC has also pledged to invest $100bn to address shortages of semiconductors over the next three years, while Nanya Technology has unveiled plans to build a $10bn plant in Taiwan.

However, the US as a whole appears more interested than concerned with the Biden administration including semiconductors as one of its four “critical and essential goods” – along with earth metals, car batteries and pharmaceuticals. While these four products are officially listed as essential, the process is for now procedural. They will be subject to an initial 100-day review followed by a more in-depth one-year evaluation focusing on the supply chains surrounding them, with the aim of ensuring the country is not exposed to such shortages in future.

“While we cannot predict what crisis will hit us, we should have the capacity to respond quickly in the face of challenges,” the government said in a statement. “The US must ensure production shortages, trade disruptions, natural disasters and actions by foreign competitors and adversaries never leave the US vulnerable again.”

What can businesses do?

Gaurav Gupta, research vice-president at Gartner, stresses the need for firms dependent on semiconductor supply to be continuously vigilant of what is and will remain a fast-moving situation. “Tracking leading indicators, such as capital investments, inventory index and semiconductor industry revenue growth projections as an early indicator of inventory situations can help organisations stay updated on the issue and see how the overall industry is growing,” he says.

Kamak advises businesses to look into reusing or recycling chips from the millions of devices and equipment thrown away each year. “In some cases, chips could be recycled from older products or circumvented altogether by reintroducing analogue models,” he says. “Not only could this help ease the burden on supply chains, it will also have a positive impact on the economy, and encourage regenerative design to reduce reliance on finite resources.”

It’s also a good time to build stronger relationships with suppliers who may have had to become selective over customers, he suggests: “In times of limited supply, organisations must build strong supplier relationships, so they can count on being customer of choice when suppliers restart production. This means giving suppliers the tools they need to collaborate in areas like supply chain planning and risk monitoring.”

Indications are that those dependent on semiconductors may be in for a bumpy ride over the next few months; something Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger spelled out in an interview with Bloomberg: “I don’t expect the chip industry will be back to a healthy supply-demand situation until 2023. For a variety of industries, I think it’s still getting worse before it gets better.”